In the previous part, I talked about Python and C, if you haven’t read that yet, check it out here.

JavaScript

The good

It’s usability: After NodeJS came out in 2009, JavaScript was no longer confined to the browser. Also because of how JavaScript is designed to be an asynchronous event-driven language, it is one of the best languages to write a server in despite it’s limitation of being single threaded. (GoLang is slowly gaining traction, with it’s Godly concurrent behaviour, but it is still far from beating the community that JavaScript has).

The community: npmjs is the world’s largest package registry in the world, which means, just like Python there is a solution for everything. From tensorflow-js to asciificator (Subtle flex, I know), you can find anything on it.

Polyfills: This term is probably alien to anyone who hasn’t used Javascript before. The idea is very simple, but has limitless implications.

It is a very common painpoint amongst developers when they have to go out of their way to work around features that aren’t available in an older version of the language (eg: You can’t use the walrus operator in Python<3.8). But in the JS world, there exist polyfills, which can “fill in” for a particular method / functionality on older systems that don’t natively support it.

The bad

- The unusual way of doing things: For anyone coming from a Python background, JavaScript takes quite a bit of time to get a hang of, because stuff doesn’t make sense.

const a = [5, 6, 7] console.log(5 in a) // output is false console.log(0 in a) // output is true A deceiving learning curve: Js might seem like a high level language which implies a small learning curve, but that isn’t the case. Javascript is a tough language to get a hold of, and it is definitely not for the faint heart. Things like prototypes, IIFEs, null vs undefined are all alien concept that could take some time to wrap your head around.

This is apart from all the other high level work that is done. Any real scale project requires you to use a lot of peripheral tools / libraries. Webpack for bundling, Gulp / Grunt for building, React / Angular / Vue for UI, Redux / NgRx for state management, TypeScript / Flow for type checking and so much more.

- The unclear role of semicolons: This is like the tab issue in Python. Whoever thought it was a good idea to allow code to be valid without them, ugh. Why? Take a look.

(function() { (function() { console.log('So') })() (function() { console.log('Annoying!') })() })()Seems normal right? Except for it isn’t. It will throw an error

TypeError: (intermediate value)(...) is not a functionWhy? (Hint: It’s a stupid semicolon 🙄)

Currently, this is how the code is interpreted:x = function() { console.log('So') }; y = function() { console.log('Annoying!') }; x()(y)();See the problem? The lack of semicolon makes it seem like the second function is chained to the return value of the first function. The problem is that the above snippet is a perfectly valid code block, which, according to me is plain dumb.

npm vs pip

It’s (very rightly) said that a language is only half as powerful as it’s community and libraries, with that the battle at one point boils down to how good the package managers are. So here goes.

- Dependency list: Oof, this is a long one.

To anyone who’s done any work with node knows about a nifty little file called package.json, which according to me is a blessing to mankind. It does an amazing job of maintaining my dependencies without me having to do any extra work. So doing something like:npm install expressensures express is added to my list of dependencies. Neat right? Trivial too.

Let’s take a look at pip then. Doingpip install flaskinstalls flask but it doesn’t do any thing other than that. If I want to create a dependency list for my environment, I’ll have to manually do it. So, runningpip freeze >> requirements.txtshould do the trick.

Well sadly, the rant isn’t over. What if I want to installanotherPythonPackage(yes, I know camelCase is against what Python stands for.), how do I add that to my requirements file?pip install anotherPythonPackage pip freeze | grep anotherPythonPackage >> requirements.txtIf your question is so what? It’s just another line yeah? Big deal? Well, yes and no.

Even though I’d really prefer having to write just one line, that isn’t the biggest problem. The problem is how pip handles the packages.

So, let’s say thatanotherPythonPackageinternally depends onsomeDependency, it’s natural to assume that it would have to be installed too right? Sure.

So what happens when I runpip freezeafter installing the package. I expect something like:anotherPythonPackage==1.0.0But instead, I will end up seeing something like:

anotherPythonPackage==1.0.0 someDependency==0.1.1And just like that my requirements file is now polluted with dependencies that I don’t really care about, because they aren’t really the dependencies of my program, they’re the dependencies of my dependencies!!

Again, you might argue that “It’s okay right? Big Deal, extra lines”, to which I say, okay. Humour me, what if the developer ofsomeDependencywakes up to realise that open source isn’t his thing, and removes it from the internet. So where does that leave my software? It leaves my software with a broken requirements file, even though I don’t really depend on it 🤬 Development Dependencies: Oh npm, you sweet sweet thing.

During development, it is almost impossible to not use supporting libraries that have nothing to do with the runtime execution of your application. You probably end up using a testing library, one for linting / formatting, something to pipeline deployment and so on. All of these don’t really matter to someone who is installing your package.

npm makes this as easy asnpm install -D somePackageand pip somehow has no support for this. If this blog ever becomes a big enough deal to reach someone who can fix this, please do.

The only work around I’ve come across in Python is to end up using 2 different requirements files. Nope, not gonna happen.- Conflicting dependencies: I have no idea on how to explain this, so I’ll just walk you through it with an example.

So let’s say you build something usingmatplotlib==2.0.0. Why? Because you felt old school.

Now you’re not an animal, so you set up a virtual environment, and all’s cool.

So:➜ test: python3 -m venv new-env ➜ test: source new-env/bin/activate (new-env) ➜ test: pip install matplotlib==2.0.0 (new-env) ➜ test: pip freeze cycler==0.10.0 matplotlib==2.0.0 numpy==1.19.0 pyparsing==2.4.7 python-dateutil==2.8.1 pytz==2020.1 six==1.15.0Apart from what we’ve discussed before, this seems normal.

Now, let’s do something else, installseaborn, which is another library for plotting data.(new-env) ➜ test: pip install seaborn (new-env) ➜ test: pip freeze cycler==0.10.0 kiwisolver==1.2.0 matplotlib==3.2.2 numpy==1.19.0 pandas==1.0.5 pyparsing==2.4.7 python-dateutil==2.8.1 pytz==2020.1 scipy==1.5.0 seaborn==0.10.1 six==1.15.0If you haven’t noticed it yet, take a look at matplotlib above. It magically switched versions, which implies, my program which was built on 2.0.0, will no longer work. 🙄

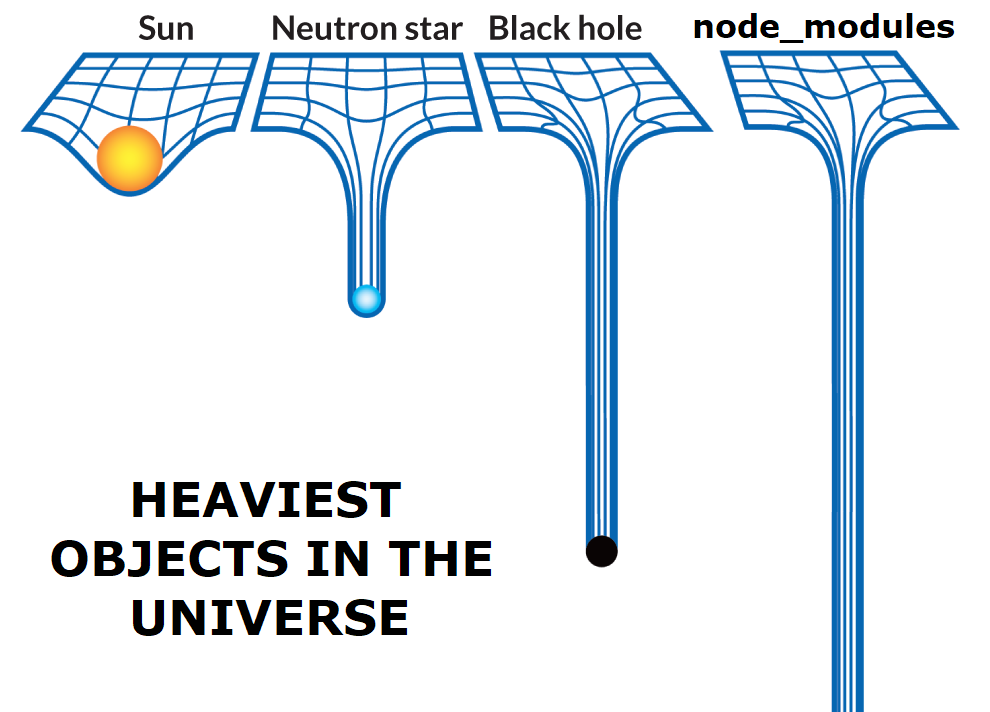

- Size: npm installs all packages in the local folder, unless explicitly told otherwise, which I feel is a better way of dealing with dependencies. But this causes other problems. Any one who’s done even a single mid size project would have at least once exclaimed at how huge the folder gets. It’s because npm recursively installs dependencies for each of your packages, and their dependencies and so on.

BUT, given a tradeoff between having broken dependencies, and a few extra MB of disk space, I’d choose the latter without a second thought.

This is all for you, for now!